A Journey Through the Tea Gardens of Northeast India

Tea has always been more than just a drink to me. It’s a ritual, a comfort, a moment of pause in the middle of chaos. But recently, I discovered that every sip of tea carries with it an untold story—of climate, communities, and countless small growers who are the backbone of India’s tea industry. This story unfolded for me during my recent field visits to North Bengal and Assam for a study to evaluate pesticide management practices in the region.

Fields of dreams – a tea garden in Jalpaiguri, North Bengal

A Legacy Brewed Over Time

India’s tea industry is steeped in tradition. It is primarily divided into the northern and southern sectors of West Bengal and Assam, with the northern belt forming the core of India’s tea production. Districts like Darjeeling, Dooars, Terai, Cachar, Darrang, North Dinajpur, Dibrugarh, Tinsukia, Golaghat, Chariodeo, Sivasagar and Udalguri are names synonymous with aromatic brews.

What stood out during my visit was the sheer magnitude of involvement by Small Tea Growers (STGs). STGs own tea plantations of up to 25 acres, although in reality, most STGs in North Bengal and Northeast India operate on less than 2 acres. And yet, they contribute nearly 50% of India’s total tea production — an astounding figure that showcases how livelihoods are delicately interwoven with the leaf.

Across Assam and North Bengal: A Tale of Two Landscapes

What struck me most during my field visit was the diversity in how tea is cultivated at the STG level. In North Bengal, the growers are scattered across districts like Jalpaiguri, Cooch Behar, Kishanganj, Dooars, Darjeeling and North Dinajpur. I walked through small plots of land once-used for agricultural crops to now converted to small tea gardens. Tea farming is also happening on even previously uncultivated patches of terrain. Some were tended by families, others by hired labour, and some operated more like structured farms with technical staff and managers.

In Assam, especially in Upper Assam districts like Dibrugarh, Tinsukia, and Jorhat, tea cultivation is part of the cultural fabric. The alluvial soil and humid climate provide the perfect conditions. Here too, many growers have built their livelihoods on previously unutilised lands, creating flourishing ecosystems one bush at a time.

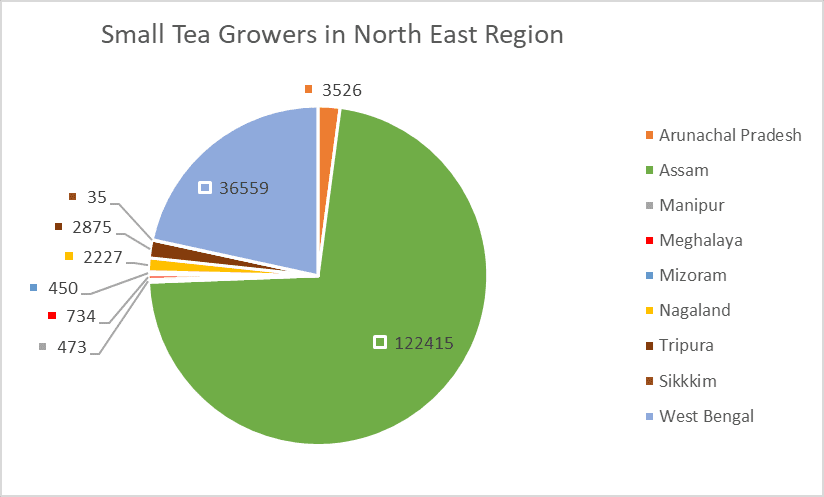

Figure 1: Small Tea Growers in North East Region (Source: Tea Board of India)

According to the Tea Board of India, Assam has over 1,22,415 Small Tea Growers (STGs), the highest in the country, followed by West Bengal with 36,559 (see Figure 1). This is not just a number, it is over 1.5 lakh stories of dedication, risk, and hope.

Together, these two states form the backbone of smallholder tea cultivation in India.

Tea Production Around the World

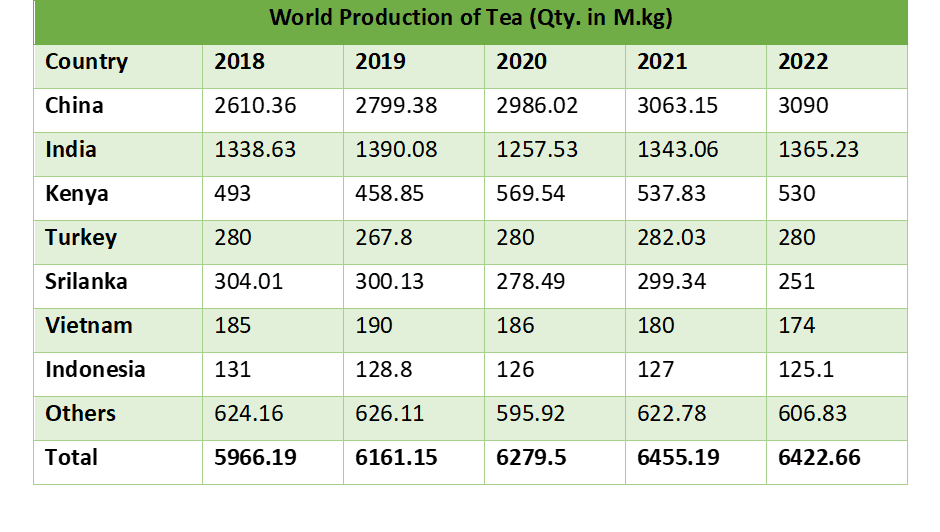

Tea is a global product, and India stands proud as the second-largest producer, just after China. A quick glance at global data between 2018 and 2022 shows China’s dominance in tea production, increasing from 2,610 M.kg to over 3,090 M.kg (see Table 1). India, despite pandemic-induced setbacks in 2020, bounced back to produce over 1,365 M.kg by 2022. It became clear to me that despite challenges, the energy in these tea-growing areas remained spirited and forward-looking.

Table 1: Showing World Production of Tea (Source: Tea Board of India)

But behind these numbers lie vulnerable communities. The people I met rely heavily on tea cultivation, yet they face numerous hurdles—from price fluctuations to the ever-looming threat of climate change.

The Concrete Jungle: An Assault of Urbanisation

Interaction with an STG in Jalpaiguri District during field survey

The tales shared were not just anecdotal—they were lived realities supported by scientific theories: unpredictable rains, scorching sun, pest invasions, and shrinking harvest windows.

I kept hearing the same concerns—rainfall patterns have become erratic, winters are warmer, and summers more brutal. ‘Pehle barish samay par hoti thi, ab toh kuch bharosa nahi’ (We used to have timely rains; now there’s no certainty). Others added, ‘We cannot afford electric machinery for irrigation due to the high costs.

Factories, Pesticides, and Difficult Choices

One of the most memorable experiences for me was walking through a tea processing factory. Watching automated rolling and drying machines hum in synchrony — a stark contrast to the humble field setups of many STGs. From mechanised sorting to sleek packaging units, these factories represent the future. But for that future to be sustainable, the raw material — green leaves — must also come from healthy, sustainable farms. Many Bought Leaf Factories (BLFs) depend entirely on STGs for their supply and some are dependent on the big project gardens. And here lies a crucial challenge—price volatility.

Tea processing factory showcasing multiple automated rolling and drying machines in Jalpaiguri

Packaging unit at Tea Factory in Jalpaiguri

Tea growers often told me about the struggle to get fair prices. Many don’t have the bargaining power to negotiate with factories. “Sometimes we sell below cost, but what choice do we have?” one grower from Biswanath district shared.

Worse still is the issue of pesticides. Pest infestations — like Oligonychus coffeae Nietner (red spider mites) and Helopeltis theivora (tea mosquito bugs) and looper caterpillars, are increasing with changing climates. To manage these pest infestations, many STGs resort to chemical pesticides. In 2024, FSSAI banned several harmful pesticides— monocrotophos, acetamiprid, Imidacloprid, acephate, dinotefuran, fipronil, cypermethrindue due to unsafe residues. Yet, on the ground, these are still being used. “We don’t always know what’s banned and what’s not,” admitted a STG based in Golaghat district. “We use what’s available, affordable and effective.”

Despite the ban, these pesticides are still being used by some growers due to a lack of awareness, supplied by local distributors, limited access to alternatives, and pressure to maintain yield under increasing pest stress.

Red Spider Mite infestation on Tea Leaves, a tea garden in Jalpaiguri

My journey through the tea gardens of West Bengal and Assam was both enlightening and concerning. If there’s one thing I came away with, it’s this: change is possible, but support is essential. Large estates are slowly moving toward organic and sustainable farming. But STGs – often without access to training, credit, or organic alternatives, need targeted assistance.

Awareness drives, subsidies, and stronger regulatory mechanisms could create a shift. The global demand for pesticide-free and organic tea is growing – India has a real chance to lead this movement, but only if we empower those who grow the tea.

Datta, Pritha and Das, Soumik, (2019).“Analysis of long term seasonal and annual temperature trends in North Bengal, India”. Spatial Information Research, 27: 475–496

https://www.teaboard.gov.in/

https://fssai.gov.in/

Author

-

Ms Shivani Solanki, Research Associate

holds a Master’s degree in Environmental Management from the Forest Research Institute, Dehradun, and a B.Sc. in Zoology from the University of Delhi. With experience across institutions like the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Wildlife Institute of India, and National Tiger Conservation Authority, she specializes in biodiversity conservation, wildlife management, and socio-economic studies and planning. Her recent fieldwork in the tea-growing districts of West Bengal and Assam focuses on traditional cultivation practices, pesticide use – including banned chemicals – and their ecological impact. Shivani brings a unique perspective on how agricultural landscapes intersect with biodiversity and long-term sustainability. Her field-based approach, combined with a strong grounding in environmental policy, positions her well to write on the environmental dimensions of tea cultivation in North East India. Beyond her professional pursuits, she finds joy in exploring new places, trekking through natural landscapes, capturing moments through photography, and actively participating in conservation activities.

View all posts