The Convergence of Nature and Culture: A Co-existence Marvel of the Junagadh Landscape in Gujarat

Growing up, when I read Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book, the idea of a human child raised by wolves, a melanistic leopard, and a sloth bear completely blew my mind. The part where Bagheera (a melanistic leopard) and Baloo (a sloth bear) take Mowgli (a human child) to a nearby village to introduce him to a human settlement— the description of the village seemed unreal for a city boy like me, almost magical. I had always wondered what living like that would feel like living in a place where animals could see you in the darkness of night; a place where nature and society co-exist, and nature is a part of their daily life and culture. I got my answers when I visited Bhavnath, a small habitation in the Junagadh district of Gujarat.

Bhavnath is situated about 8 km away from Junagadh city, nestled at the foot of the Girnar mountain, and most importantly, amid a rich, flourishing dry deciduous forest. I visited Bhavnath during Maha Shivaratri, a grand 3 day celebration in the region. The festival is considered special in Junagadh, carrying strong religious beliefs. According to the local legends bathing in the ‘Mrigi Kund’ what is it at midnight, brings salvation to devotees, and a procession of Nagabavas (a revered, often naked, ascetic warrior within Shaivism (followers of Lord Shiva) in Hinduism, known for renouncing worldly life and practicing extreme austerity), takes place to benefit from the spiritual opportunity.

Though captivating, and filled with saints, music, dance, and delicious food, my mind was fixated on the fact that thousands of people had gathered amid prime Asiatic Lion territory, and how vulnerable both species must be to each other. It reminded me of how Bagheera and Baloo, two apex predators of the jungle, could come so close to the villagers and watch them but not harm them. What if a couple of lions were watching us too right now?

After speaking with forest rangers, district officials, and the veterinary officer of the Girnar area, I realised that the story ran deeper than I had imagined. There is an entire mechanism that manages this natural and cultural convergence. Forest guards, rangers, veterinary doctors, and officials work day and night to ensure the mela is safe and successful. Several routys (temporary forest outposts) are set up by the forest department, each manned by 7–8 rangers, ensuring continuous monitoring. These posts are positioned at potential human- wildlife interaction zones and are also responsible for checking forest fires and managing plastic waste disposal. I was amazed to see dedicated frisking points at every forest entry, where single-use plastic was thoroughly checked and immediately discarded into bins if found. The effort to maintain both religious sanctity and ecological health was commendable.

An engaging conversation with the forest guards on monitoring of the mela and the forest

Interestingly, forest rangers rarely encounter lions near village edges or forest boundaries. When I raised this with the veterinary officer, Dr. Riyaz Kadiwar, he explained that lions are highly perceptive animals that tend to avoid areas of human congregation, such as the mela. According to him, it is usually only curious sub-adult or ‘teenage’ lions that occasionally wander close to boundary areas. “They are more excitable and exploratory at that age,” he noted, adding that if such situations arise, rangers promptly guide them back to their pride.

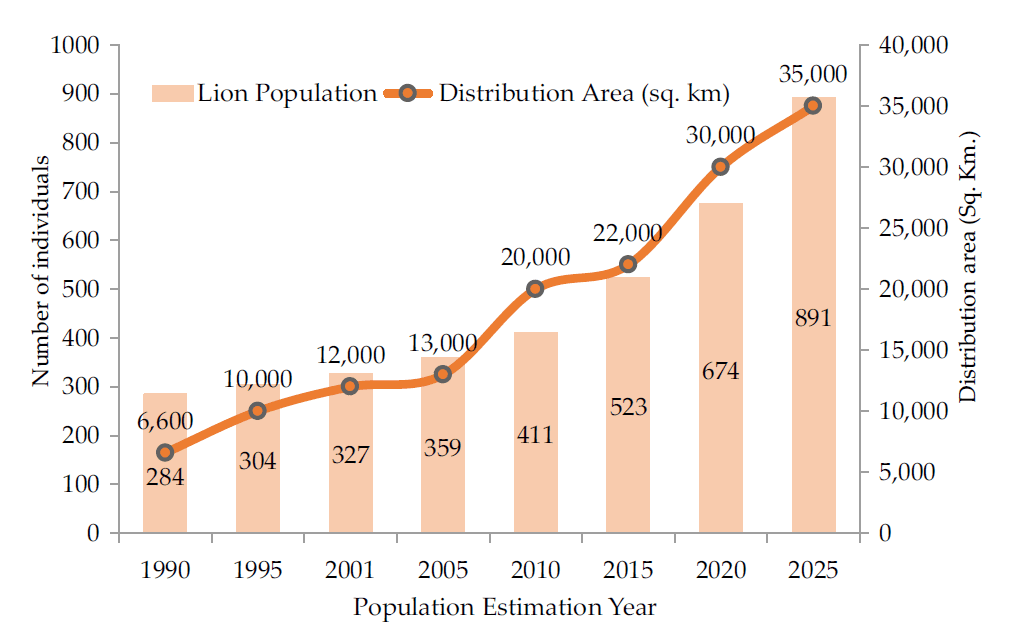

When asked about the risk of poaching during lion movement between Girnar and Gir, Dr Kadiwar emphasised that such threats are minimal, as local communities do not harm the species. He attributed this to strong cultural beliefs, explaining that the lion is revered as the vahana (vehicle) of Goddess Amba. This deep-rooted cultural association has played a significant role in conservation outcomes. Over the past few decades, India’s lion population has increased markedly—from 284 individuals in 1995 to 891 in 2025—demonstrating how the integration of cultural values has been a vital contributor to their protection and recovery.

This is not uncommon in India. Nature has always been a part of culture, religion, and festivals in this diverse country. Many of these festivals are based on natural phenomena ranging from the changing seasons, harvest times, to the sun’s movement. When people revere nature and wildlife as something sacred and divine, it creates a powerful foundation for conservation. To name a few: the Indian cow is often venerated as Gau Mata or Mother Cow in Hinduism and is seen as a symbol of peace and non-violence because of its calm demeanour. Communities like the Dangis in Gujarat and the Gonds in Madhya Pradesh worship the tiger as a deity or guardian spirit often referred to as Waghoba or Bagheshwar. Elephants are revered due to their association with Lord Ganesha, one of the most worshipped deities in Hinduism, symbolising wisdom and auspiciousness. Even the aquatic apex reptile, the crocodile, is associated with deities like Goddess Ganga (the sacred river deity) and Varuna (hindu deity of the oceans, water and cosmic life) and is prayed to in some regions.

This cultural reverence isn’t just symbolic, it often translates into real-world conservation. Across many regions, communities have been protecting nature long before environmentalism became a formal discipline. Their efforts weren’t driven by obligation but by a deep-rooted connection to their surroundings much like how one protects and nurtures their home, especially if they’ve built it themselves. In safeguarding forests, water bodies, and sacred groves, they have also preserved countless microhabitats for a wide range of species.

Examples from beyond India further echo this sentiment. In Madagascar, caves considered sacred due to their spiritual value became unintentional sanctuaries for bat populations. The Pemba flying fox (Pteropus voeltzkowi), endemic to the island, gained protection not only through modern conservation awareness but also because of animist beliefs that revered the species. These beliefs, coupled with scientific insights on its population decline, motivated village elders to introduce local bylaws that limited disturbances and hunting. Such examples underline how cultural respect for nature can lay the groundwork for ecological resilience.

The takeaway from Bhavnath, and countless other places like it, is clear: successful conservation doesn’t come from isolating nature from people, it comes from including people in the story of nature. Communities, with their beliefs, traditions, and lived experiences, are not threats to conservation but its oldest allies. When religious reverence and cultural identity are interwoven with ecological awareness, they create a durable, grassroots foundation that modern conservation alone cannot replicate. Efforts that respect and build on this relationship rather than dismiss it stand a far greater chance of being sustainable. The key lies in collaboration: in walking with communities, not ahead of them. Because the forest has never truly been separate from the village, and our path forward must reflect that truth.

Author

-

Mr Aakash Chaturvedi applies his expertise in biology, environmental sciences, and ecology towards the public policy and environmental sustainability projects at Sankala. He holds a Bachelor's degree in Biochemistry from the Amity Institute of Molecular Medicine and Stem Cell Research and a postgraduate degree in Environment and Development from Dr BR Ambedkar University, New Delhi.

View all posts