From Flooded Streets to Sponge City: Sankala’s Blueprint for a Water Resilient Gurugram

Gurugram is often spoken about in terms of flooded junctions and declining groundwater. At Sankala Foundation, we see it as something more hopeful: a living laboratory where a fast-growing Indian city can relearn how to behave like a sponge, absorbing, replenishing, and restoring its natural water systems. With the support from Denmark Embassy, through the Denmark–India Green Strategic Partnership, the Sankala Centre for Climate and Sustainability (SCCS) is designing an urban rainwater management model that is as much about people and institutions as it is about drains and pipes.

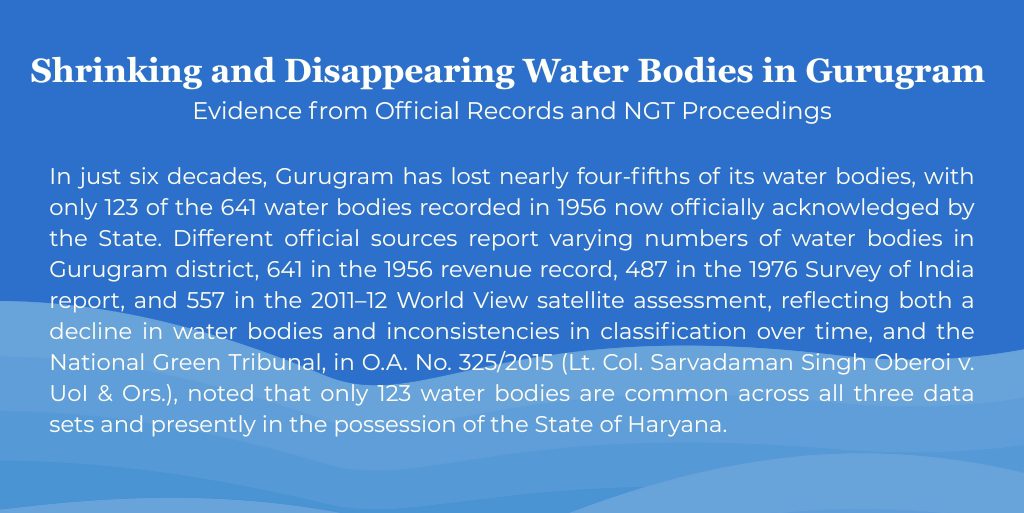

At the core of this work is a simple premise: if Gurugram is to live with the monsoon rather than fear it, it needs systems that can hold, slow, infiltrate, filter, and reuse the water it receives, instead of pushing it out as fast as possible. Our study for the project begins by looking closely at the city’s hydrology. Using GIS and field surveys, we map drainage networks, flood hotspots and recharge potential across key sectors – from the Aravalli ridge where intense runoff starts, to the low-lying basins near the Najafgarh drain, where city wastewater now spreads over thousands of acres. This diagnostic phase will create a baseline: where water comes from, where it gets stuck, where it disappears underground, and where small interventions can make the biggest difference.

Together with local authorities, Sankala plans to develop a locally suited, integrated model that combines nature-based solutions with carefully chosen engineering measures. In practice, this will mean piloting permeable pavements on streets that currently behave like flumes, introducing bioswales and raingardens along edges of parks and institutions, and creating “sponge ponds” that can safely store stormwater while recharging groundwater.

In residential and institutional campuses, Sankala Foundation will work with Gurgaon municipal authorities to coordinate the setting up of Resident Welfare Association (RWA) led decentralised rainwater harvesting and recharge systems, and to use surplus treated water to keep small ponds and greenbelts alive even outside the monsoon.

An RWA-led initiative

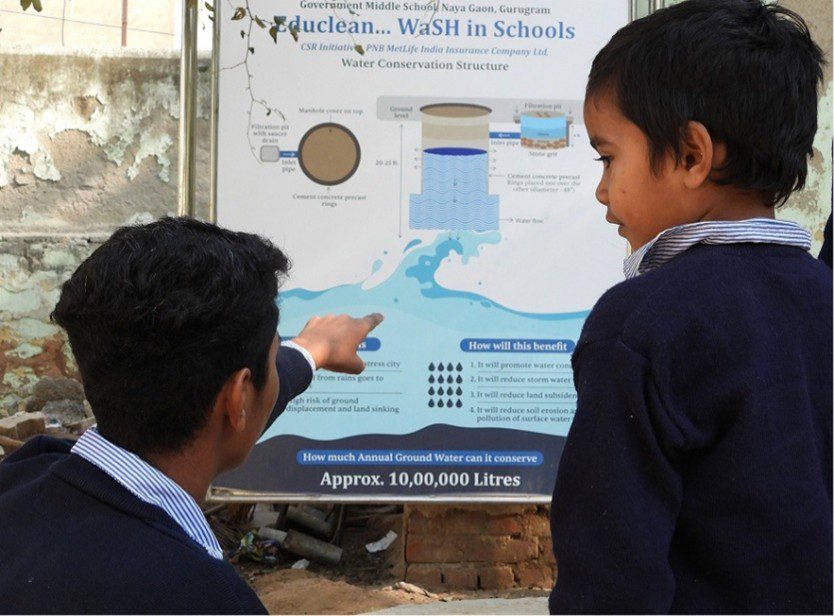

Equally important is the human side of the system. Sankala’s partnership model places RWAs, corporates, community groups and frontline officials at the centre of the work. Training workshops and on-site demonstrations will help the communities understand what it means to turn a park into a dual-use flood and recharge field, or how to maintain a small bioswale along a boundary wall. Municipal engineers and urban planners will be invited into the process early, so that lessons from pilots can inform design standards, zoning norms and future projects rather than remaining isolated experiments. Academic institutions and civil society organisations will contribute research rigour and local knowledge, helping connect city-scale strategies with neighbourhood realities.

The project also looks to learn from international examples, including cities that have begun to treat stormwater as a resource rather than a waste stream. Approaches such as cloudburst streets, green–blue corridors and distributed retention basins will not be copied wholesale, but carefully adapted to Gurugram’s soils, slopes and social fabric. The aim is to blend emerging global best practices in sustainable urban water management with Indian planning contexts, so that the model remains both globally informed and locally rooted.

The work is structured in three phases

- The first is diagnostic: building the hydrological picture, listening to residents, identifying hotspots and opportunities.

- The second is pilot design and implementation in selected urban zones, where multiple interventions – nature-based, grey and digital – can be tested together.

- The third is replication: working with GMDA, the municipality and state agencies to integrate what works into municipal plans, standards and budgets, so that the model can scale to other sectors in Gurugram and, eventually, other rapidly urbanising districts in Haryana.

If this vision holds, the impact will be felt in many ways. Flooding and waterlogging in known hotspots should reduce in frequency and severity. Groundwater levels, especially in neighbourhoods where recharge structures are introduced, can begin to stabilise instead of relentlessly dropping. As more treated wastewater is routed to green spaces and restored ponds, the pressure on freshwater sources can ease, and the city’s green cover can become more resilient to heat and drought. Perhaps most importantly, communities will have a stake in the systems that protect them: RWAs managing their own small ponds, school children learning to read a rain gauge, engineers and residents using the same dashboard to decide when and where to intervene.

For Sankala Foundation, Gurugram is thus not only a site of crisis but a proving ground. It is where a new kind of partnership, between global expertise and local nuance, between institutions and neighbourhoods, between grey and green, can show that even a hard- edged, high-speed city can rediscover how to live with water, and in doing so, lay the foundations of true urban resilience.

Author

-

Mr RK Srinivasan is Programme Lead (Water Resource Management) at Sankala Foundation. With over 20 years of experience in the sector, Mr Srinivasan leads and steers the strategic design, research and monitoring of water resource management initiatives, advancing policy advocacy to strengthen water security, climate resilience, and inclusive service delivery across rural and urban systems.

View all posts