More Than a Forest: The Living Culture of the Aravalli

Living with the Forest

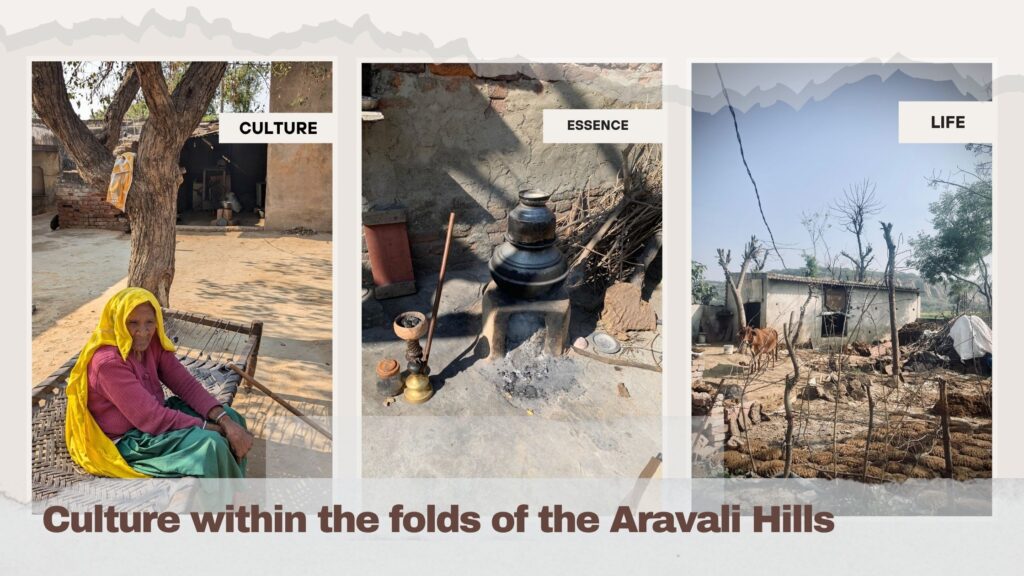

I have been working on an ecorestoration project, in Sankala Foundation, for which our team planned a visit to the Aravali forest in Gurugram District. As we made our way to a forested patch of the Aravalli Range, near Sakatpur village, Gurugram District, my thoughts were on the leopard trail ahead.The anticipation of birdsong, the possibility of spotting wildlife. But just before the trail began, the scene shifted. An elderly woman gathered firewood, a shepherd tended to his goats, and the forest edge revealed a community moving in quiet harmony with the land. Nearby, women in bright traditional attire were singing around a village well. It was ‘Kuan Poojan’, a local ceremony where prayers are offered for water and blessings for a newborn. They were eating flat-breads fresh off the traditional wood-fired stove. A simple fare, deeply rooted in place. The attire, ghagra, orhni, (long skirt and a long scarf) for women and, dhoti (loincloth worn by men in the Indian subcontinent, typically wrapped around the waist and legs), kurta (long, collarless tunic or top), and a pagri (turban), for men, were shaped not just by custom, but by the very climate and soil they live on.

It made me pause and reflect: what does it mean to live with the forest? How do culture, livelihood, and identity evolve when nature isn’t just background, but belonging?

Where Culture and Ecology Intertwine

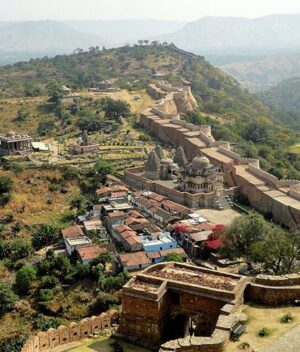

The Aravalli range is not just a forest but a confluence of a unique cultural and economic amalgamation between nature and its inhabitants. Dwelling communities, pastoral groups, and agrarian societies have relied on these forests for sustenance, medicinal herbs, and traditional crafts. Today, the quiet symbiosis between people and landscape in the Aravalli range is under threat. The concretisation of cities like Gurugram is swallowing the ancient contours of the aravalli hills. While development has its place, its unchecked spread has left both ecosystems and communities gasping. As per the Forest Survey Report 2023, 30% of forest cover of the aravallis has already disappeared in a couple of decades; it is lost to deforestation, urbanisation, and urban encroachments. The depletion of these forests destroys more than than trees, it severs communities from their land, culture, and essence. The deities once worshipped in forest groves are forgotten in urban landscapes, and traditional festivals lose their vitality as ecosystems decline. This is more than environmental destruction. It is the loss of culture, history, and meaning!

Depleting ground-water and water wisdom of aravalli range

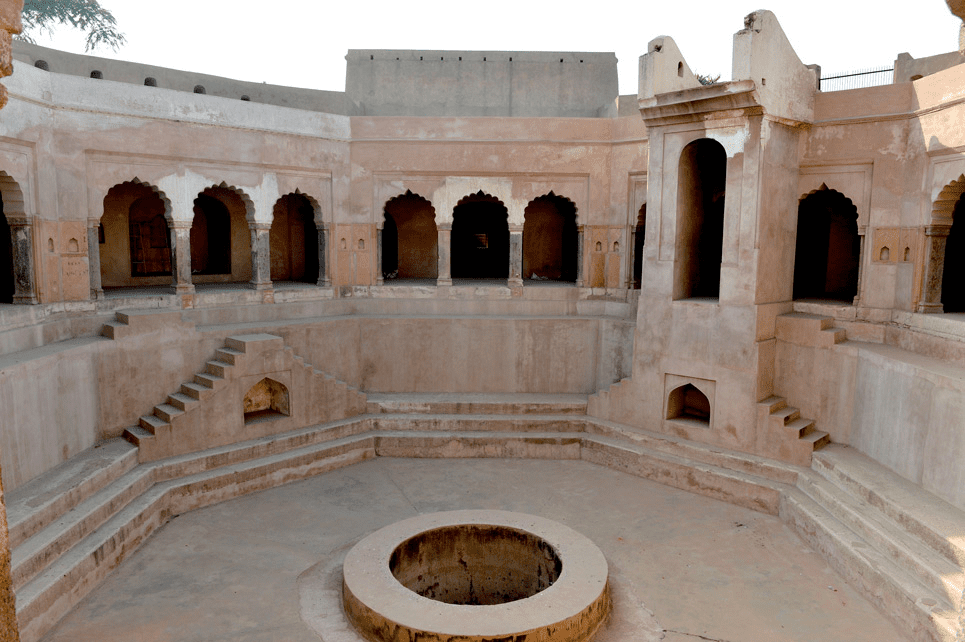

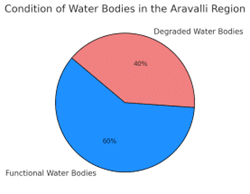

According to the Central Ground Water Board (2022), 40% of the Aravalli region’s traditional water bodies, including ancient ‘johads’ (ponds) and ‘baolis’ (step-well), are now dry or severely degraded. These structures, once vital for water storage and community survival, are disappearing as unsustainable urban demand drains groundwater.

Gurugram district has several stepwells., Like Baoli Ghaus Ali Shah and the octagonal well in Farrukhnagar. These structures stand as reminders of the region’s historical water wisdom. But today, beyond their heritage value, they serve only as dry echoes of a time when water once flowed through their stone veins.Image Source: Haryana Tourism

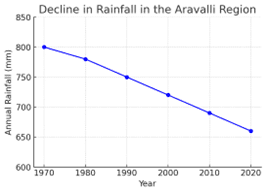

Rainfall patterns are also shifting. Data from the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) shows that the Aravalli region has seen a 10-15% decline in annual rainfall over the past 50 years. Monsoons, once predictable, now deliver 500-700 mm of rain in erratic, intense bursts, disrupting agriculture and groundwater recharge. The impact ripples beyond water tables, agriculture falters, daily needs go unmet, and centuries-old practices around water worship, like the Kuan Poojan I witnessed are strained by the growing absence of what they honour.

The consequences are severe: vanishing water sources, declining crop yields by almost 50% , and threatened livelihoods. Without urgent action, both ecosystems and communities face irreversible losses.

A 10-15% rainfall decline over 50 years (IMD)

This is just one glimpse from Haryana. The Aravalli range extends to three states and a union territory – Haryana, Rajasthan, Gujrat and Delhi. Each clasping its own milieu of culture, woven over centuries in response to the local climate, geography, and the simple joy of living. But with this depleting forest cover and rapid urbanisation, we are losing all of this.

An elderly woman reminisced about ‘Saavan’ (Hindu calendar month around July). Savan was the monsoon month when peacocks squawked and danced, and courtyards bloomed with jhulas (swings) tied to trees. It was a season of joy, marked by community gatherings, songs, and prayers for loved ones. During Haryali Teej, women dressed in vibrant clothes would sing folk songs and dance, celebrating the lushness of life. “Now,” she sighed, “there’s no real monsoon anymore… and children don’t care for these customs.” The songs she once heard from her mother, passed down like heirlooms will soon vanish, unheard by the next generation.

The Aravalli’s forests, once alive with the rustle of leopards (Panthera pardus) and the dawn-lit silhouettes of nilgai (Boselaphus tragocamelus), are thinning. Medicinal plants like Giloy (Tinospora cordifolia) and Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) are vanishing, and as traditional knowledge fades, fewer people seem concerned with what’s being lost. Villages empty into chaos, their folk-songs of wells and monsoons replaced by the static of construction. Livelihoods once rooted in this soil, the hum of looms, the chipping of lac, the careful drying of herbs in courtyards are now slowly vanishing. These rhythms have quietened. As forests retreat and water turns scarce, so do the trades that once drew from them. The changing workforce has transformed the sustainable livelihood people practiced. In parts of Haryana’s Aravalli region, traditional livelihoods such as animal husbandry, rain-fed agriculture, and craft-based activities like lac work and pottery are under pressure due to ecological degradation and shifting labour patterns.

A Shifting Landscape: Work, Migration, and Memory

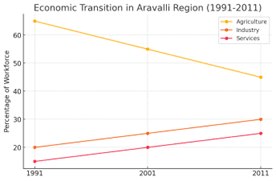

As per the census data, in the 1970s, nearly two-thirds of the region’s people worked the land. By 2011, only 40% remained tied to farming. The rest have moved some to towns, others into industries, in search of survival. Migration now has a pattern: men leave seasonally for construction sites, women join self-help groups or service jobs, and youth drift between aspiration and displacement.

The line graph captures the dramatic shift in employment patterns in the Aravalli region over four decades. While agriculture once employed 65% of the population in 1971, this has dropped to just 40% by 2011, with more people moving toward industry and services. However, the rise in marginal employment signals economic vulnerability among rural communities. (Source: Census data https://censusindia.gov.in)

Many have begun to ask, “can old skills find new ground?” And maybe they can. Women’s collectives in many parts of India have begun turning forest fruits into jams and pickles , reweaving the cultural economy. Folk singers once confined to village squares now find global audiences online. Even crafts once endangered, from hand woven rugs to terracotta figurines, are finding lifelines in eco-tourism and digital markets.

If the forests go, what follows is not just ecological loss; it’s the fading of memory, music, and meaning. Aravalli’s restoration, then, is not just environmental work. It’s cultural preservation. The Aravalli is changing and the people around have to learn to adapt, like a melody, it can change in tune, not in silence.

The Aravalli stands today like an ancient pakhawaj drum, its skin stretched thin by time, its rhythms fading, but still holding the memory of every beat. If we listen closely, the land whispers its needs: not just the water to fill its rivers, or the trees to shade its soil, but the hands that know how to play its song before the silence sets in.

Author

-

Ms Utkarsha Rathi has a strong academic grounding in botany and environmental sciences, Utkarsha brings a wealth of research experience to her analysis of the Aravallis. Her involvement in significant projects, including leading research on medicinal plants, demonstrates a deep understanding of the region's natural resources. This scientific insight is complemented by her practical work in the WASH sector, providing a crucial understanding of the interplay between human needs and environmental realities. Her Master of Education further enriches her perspective by informing her understanding of socio-cultural learning and knowledge systems within the Aravalli communities.

View all posts