Corbett’s Writings Help us Reconnect with the Natural World

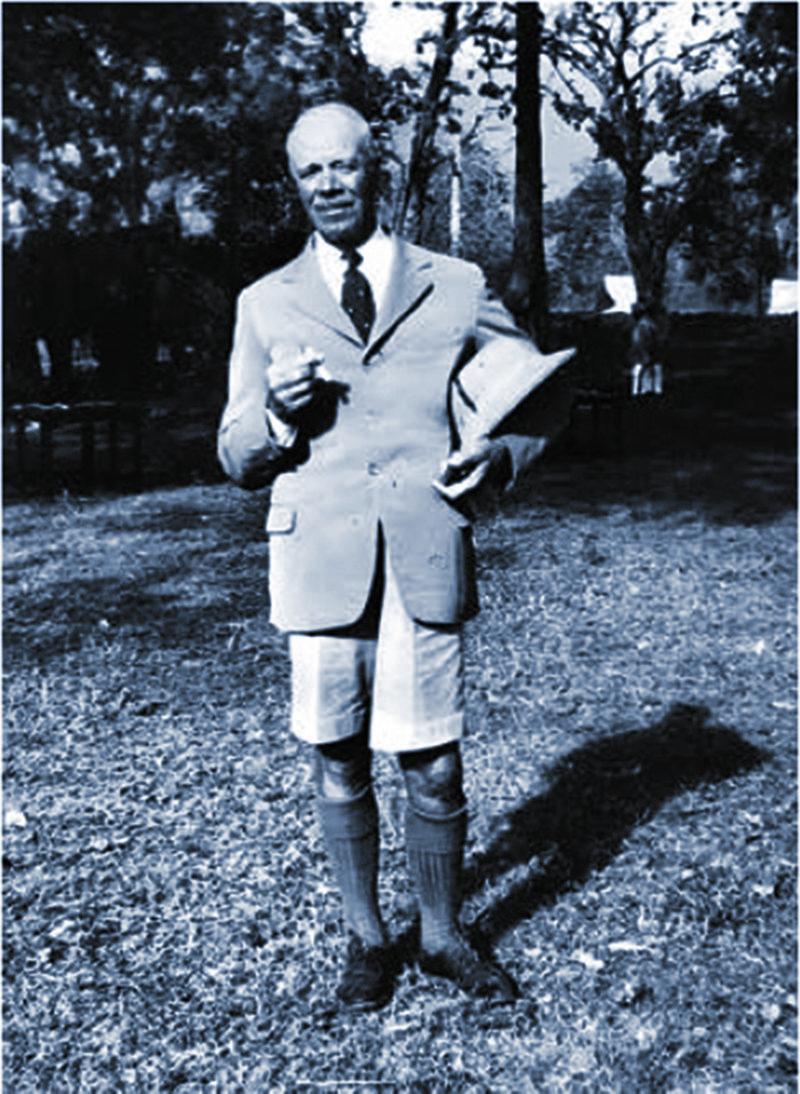

Edward James Corbett’s writings are a treasure for India and the world. Born on 25 July 1875 in India, almost 100 years before tiger conservation was launched as a national project, his explorations of the Indian jungles (Himalayan foothills) and his experiences of hunting, killing and protecting the big cats offers a fascinating study in wildlife preservation.

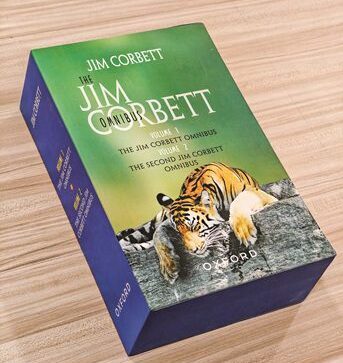

The Oxford University Press’s The Jim Corbett Omnibus – Vol 1 and 2 is a wonderful assemblage of some of Corbett’s best known and rare works. The two volumes are divided between his bestselling books Man-eaters of Kumaon (first published in 1944), The Temple Tiger and More Man-eaters of Kumaon, The Man-eating Leopard of Rudraprayag and less quoted My India, Jungle Lore, and probably his last published writings Tree Tops (set in Kenya).

The first collection elaborates some of his hunting expeditions – between 1907 and 1938. He is known to have killed more than a dozen tigers and an equal number of leopards. All his kills had extensively threatened human life in the villages of the state of Uttarakhand in northern India. His writings not only carry the suspense and rigour of chasing and hunting fierce animals, but also an appeal for restraint and care – he marvels at the beauty of the forests and is one of the first to record the consequences of rapid takeover of the forest by human habitation.

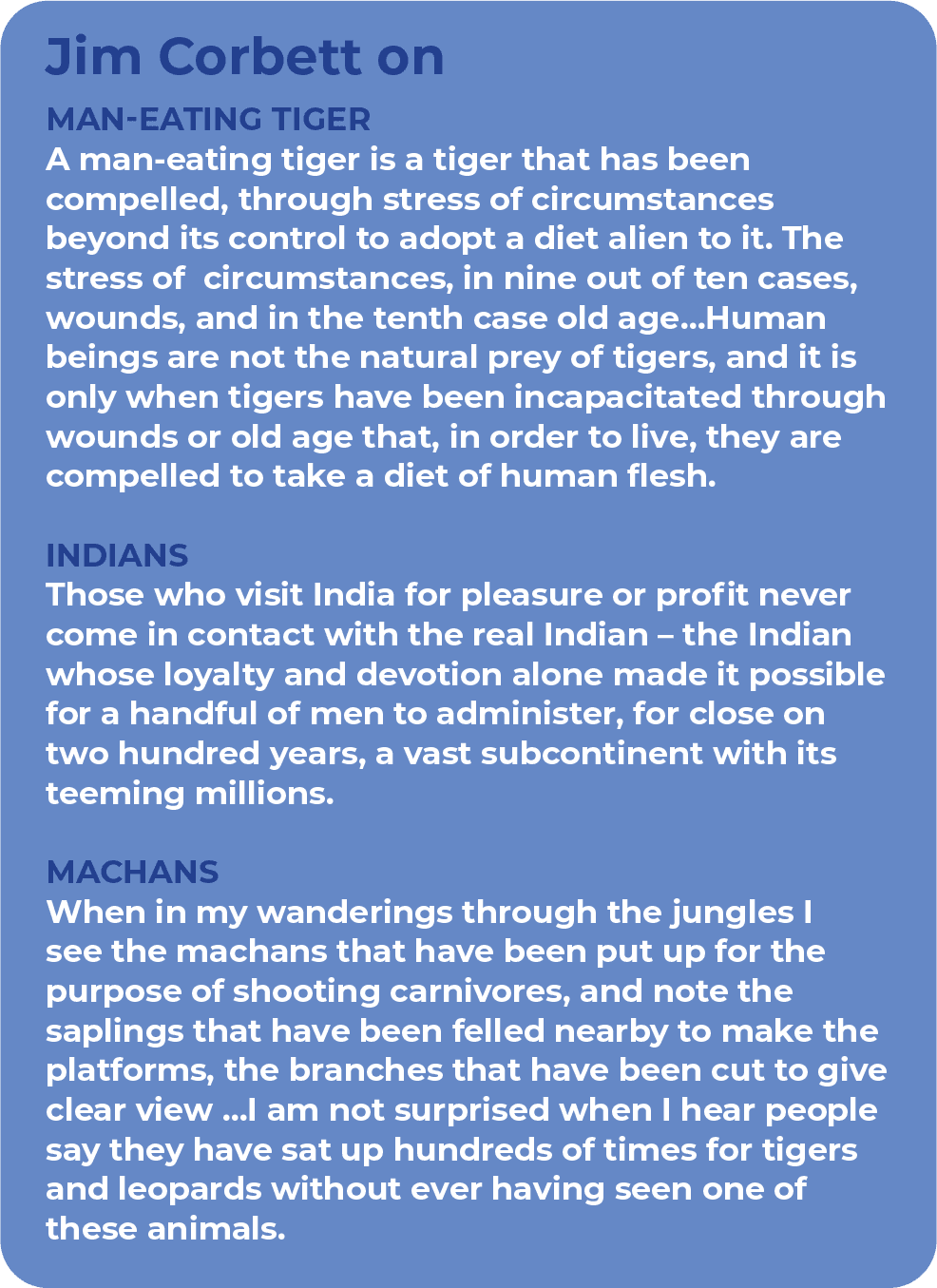

A large part of Corbett’s writings in this volume avoid demonising the tiger, especially the ones considered as man-eaters. He challenges expressions like ‘cruel as a tiger, ‘bloodthirsty as a tiger’, while recounting his personal encounters with the big cat. The tiger, unless molested, would do no harm. Even after more than three decades of pursuit of man-eaters, Corbett claims in the Author’s Note that he does not recall any moment when the tiger had been deliberately cruel, or killed without provocation.

Corbett was concerned, as early as the mid-1930s, of the threat to tiger habitat that may result in extermination of the marvellous species. Many of his books are evocative long-form fables warning about the damage to wildlife and especially to the tiger. In the early 1970s, his predictions of the tiger disappearing from the forests almost came true when tiger population hovered just around 2,000.

Master of the Jungle

In Volume 2, readers come face to face with Corbett the child, and the man. By the time he is 11, Corbett has learnt three valuable lessons in jungle training – he can fire a gun, has gone deep inside forests to see tigers and bears, and has learnt that there is no danger from wild animals that are not wounded. His brother Tom, his friend and guide, often lured him to explore the hidden corners of the forest. Once when he was seriously ill and unable to eat, Tom presented him with a catapult. The gift was followed by a cup of beef juice. He had to drink the juice in order to be strong to use the catapult. Corbett took the bait.

By the time Corbett reached his teens, he could make sounds of various birds and animals – a langur or cheetal barking, a peafowl calling at a tiger. Corbett later credits his ability to pinpoint every sound in the jungle as a special skill that helped him assess the movement of the unseen tigers and leopards. He describes his progress as hunter: “Fear has taught me to move noiselessly, climb trees, to pin-point sound; and now in order to penetrate into the deepest recesses of the jungle and enjoy the best in nature, it was essential to learn how to use my eyes, and how to use my rifle.”

Corbett, the man, was generous and smart. He helped a lower caste get rid of his long debt; saved his close friend Kunwar Singh from opium addiction; and crowd-funded support for the family of a headman. He writes movingly about Sultana, a tribal forced to take to crime. He regrets the British government executing Sultana, for he did not have a fair chance as he was branded a criminal since birth. Many of the stories in this volume demonstrate his deep love for the people and the desire to work for their happiness. He describes Indians as big-hearted and predicts that one day they would “weld the contending factions into a composite whole, and make of India a great nation.”

In Tree Tops, named after a hut built on the branches of a Ficus tree in Kenya, Corbett details the visit of Queen Elizabeth (then a princess). The hut is accessible by a steep and narrow 30-foot ladder. From the balcony of the hut (equipped with a dining room, three bedrooms) one could get a clear view of the miniature lake and Aberdare mountains rising to a height of 14,000 feet. Elizabeth stayed in this hut along with Prince Phillip. Corbett’s account presents her as keen student of wildlife and conservation. This was no ordinary visit. Corbett writes: “For the first time in the history of the world, a young girl climbed into a tree one day a Princess and, after having what she described as her most thrilling experience, she climbed down from the tree next day a queen.” Her father King George VI died while Elizabeth was in Kenya.

The two volumes, dotted with several illustrations, carry an old-world-charm. An editor’s note on why some of these works were included and others excluded in the omnibus would have added to the value of the two volumes. Even more wonderful would have been inclusion of some photographs of Corbett and his life in India.

Undoubtedly, Corbett’s words continue to speak to us, about our rich biodiversity, and implore us to protect it. Most importantly, they help us reconnect with the natural world, and realise the advantage we have in building our relationships with the wild.

This article was originally published in July-August 2025 issue of the BigCats Magazine. Subscribe to BigCats Magazine and receive your own copy Here.

Author

-

Dr Malvika Kaul is Director (Research & Communications) at the Sankala Foundation. She has over three decades of experience spanning academia, journalism, publishing, and the development sector. She has worked with leading institutions such as Times of India, The Indian Express, ActionAid, Plan International, and UNICEF, and collaborated with top universities including NYU Steinhardt. A recipient of the international Panos fellowship for her research on women’s use of technology for economic empowerment, she leads Sankala’s research, documentation, and editorial initiatives.

View all posts