Tigers' conservation can support water security

India’s tiger conservation strategy focuses on recovering the wild tiger population, which serves as an umbrella species. Conserving tigers contributes to the protection of diverse forest ecosystems, as well as wetlands and grasslands.

A recent study, published by the Sankala Foundation in collaboration with the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA), titled "Stripes and Streams: Water Conservation in India’s Tiger Reserves," explores how tiger conservation efforts have impacted the interconnection between forest and water ecosystems. The outcomes show that conservation efforts in the 53 tiger reserves have enhanced water availability along 21,036 km of rivers and 33,248 km of streams within the tiger landscapes. The tiger reserves are also vital in delivering water services to around 340 million people and a large agricultural area covering approximately 19 million hectares across 18 states in India.

Healthy forest ecosystems have a significant impact on hydrology, as they play a crucial role in shaping water systems. Therefore, forested landscapes, including those with wetlands and grasslands, are vital to the water cycle. They control streamflow, enhance groundwater recharge, and contribute to atmospheric water recycling, including cloud formation and precipitation through evapotranspiration. They also function as natural filters, reducing soil erosion and water sedimentation, thus maintaining high water quality.

Tiger reserves represent some of India’s most ecologically valuable forested landscapes, encompassing diverse ecosystems such as forests, grasslands, and wetlands. These habitats act as natural sponges, absorbing rainfall and recharging aquifers while preventing river sedimentation. Additionally, they play a critical role in minimising the risks of water-related disasters, such as floods and droughts, and in combating desertification and salinisation. Indeed, as apex predators, tigers symbolise healthy ecosystems that provide critical services, including water regulation and soil conservation.

Approximately 600 rivers in India originate from or pass through the catchment areas of tiger reserves, helping to regulate water flow by allowing rainwater to soak in, reducing surface runoff, and supporting river base flow during dry periods. Rivers such as the Godavari and Krishna, which originate in the forests of Central India, depend on forested catchments that overlap with various tiger habitats. The Western Ghats are vital tiger habitats that regulate streamflow and water cycles in watersheds, hosting 16 important rivers, including the Cauvery and Nethravathi, which are crucial for local and regional water security. The Western Ghats are a mountain range that stretches 1,600 km along India’s western coast, approximately 30-50 km inland, traversing the States of Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu.

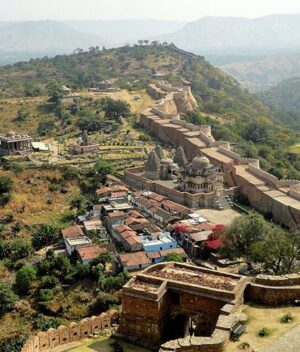

Therefore, conserving tiger landscapes is essential for ensuring the sustainable management of India’s water resources, which are vital for maintaining ecological balance and fostering human prosperity. For example, the Ranthambore Tiger Reserve in Rajasthan conserves water that benefits nearly 300 villages in an arid region of Rajasthan. Moreover, the Periyar River, which originates in the Periyar Tiger Reserve, supports the water requirements of Kerala and southern Tamil Nadu. Additionally, a study published by the NTCA estimates that benefits related to water provision from 10 tiger reserves amount to over ₹330 billion (US$3.74 billion) annually.

In 2017, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) reported that the forested catchments of the Corbett Tiger Reserve, along the Ramganga River, provide crucial services for downstream areas of Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh. From 1974 to 2010, a downstream dam generated significant economic benefits, including US$41 million worth of electricity and 88,000 million cubic metres (m³) of irrigation water, without requiring direct investment in catchment treatment or major siltation. By the early 1990s, the Tamirabarani River of Tamil Nadu had started to dry up. Its revival occurred after the declaration of Kalakkad-Mundanthurai forest as a tiger reserve in 1992, which aided the tiger population in the area and enhanced the conservation efforts for the river.

India’s overall water demand is rising, with agriculture being the largest user, accounting for around 85% of the country’s total freshwater consumption. The country faces a growing seasonal water shortage; by 2030, projected demand is expected to exceed the available supply, potentially impacting millions of people and numerous economic activities. Indeed, investing in tiger conservation by protecting approximately 2.5% (about 84,487 km2) of the total land area (tiger habitat) has contributed to India’s water security. The country still has about 380,000 km2 of potential tiger habitat outside the purview of Project Tiger.

Bringing these potential tiger habitats under the umbrella of the Project Tiger will help safeguard river and forest ecosystems, which in turn could contribute to addressing future seasonal freshwater shortages in the country.

Author

-

Dr Pramod holds a PhD from Clemson University, USA, and applies conservation social science to policy, governance, and sustainability research. He leads research and advocacy on sustainable livelihoods, wildlife management, biodiversity conservation, and socio-ecological systems. His work strengthens conservation efforts for seven big cat species across 96 range countries.

View all posts