When Asiatic Lions Reclaim their Lost Home

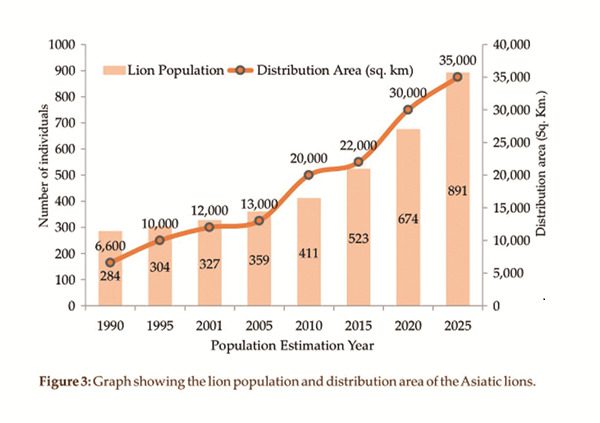

India has 891 Asiatic lions in the wild today. Since 2020, there has been around 32% increase in their count. The May 2025 Asiatic Lion Population Estimation (the 16th since its inception in 1968) not only affirmed the presence of a stable population but also offered evidence of the apex predator reclaiming lost territory. The survey also pointed towards substantial reduction in human-wildlife conflict, a unique example in conservation history.

The Asiatic lion (Panthera leo persica) once roamed extensively across Asia Minor and in parts of Arabia, Persia and the Indian subcontinent. But by the 17th century its range had shrunk, confining the big cat primarily to Asia Minor (Turkey) and western India. The decline was rapid in the forthcoming decades – the species was extirpated from Turkey by early 19th century, it had vanished from Iraq during the First World War, and was eliminated from Iran in the Second World War. This was largely due to intensive hunting, habitat loss, and human encroachment.

By the mid-20th century, the Asiatic lion’s range was confined exclusively to Saurashtra, the peninsular region of Gujarat, a state in western India. Even in India, the situation appeared critical when in 1968 during the first lion estimation by the Gujarat Forest Department, only 177 individuals were recorded. And they were all restricted to the Gir Forest region (enclosing the Gir National Park and Wildlife Sanctuary). Conservationists feared that this remnant population — the last wild Asiatic lions on planet Earth — would also disappear within a generation if urgent actions were not taken.

Expansion of Territory

This concern galvanised Indian authorities and scientists and since the 1970s, the state of Gujarat spearheaded one of the most successful large carnivore recovery programmes in the world. Hunting lions had already been banned in 1965. India enacted the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, which provided a nationwide legal framework for protecting endangered species, including the Asiatic lion. Lions were included under Schedule I — the highest protection category in India’s Wildlife Protection Act, 1972.

Conservation efforts were scaled up with systematic population estimation undertaken every five years. Anti-poaching units and veterinary care units were set up and community outreach programmes were also initiated. These efforts not only increased the lion numbers, but also expanded their range from the dry teak forests of Gir to the grasslands and coastal regions of the state. Significantly, this habitat expansion was achieved without displacing local communities or affecting their livelihoods. The lion population grew from 180 in 1974 to 327 in 2001, and 523 in 2015. And in 2025, it reached 891 individuals. This has been a gradual and steady rise.

Eco-restoration with Eco-development

The success of this could be attributed to the twin focusses of eco-restoration and eco-development. In 1974, the Gir Wildlife Sanctuary was officially notified under India’s Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, covering 1,412 km². It marked a watershed moment: the area was protected as a sanctuary, with core and buffer zones, and a lion population estimation began under scientific protocols. Around 82 villages, mostly inhabited by pastoral communities like the Maldharis, and the Siddis (an ethnic group originally from Africa), came within the Gir Protected Area (PA). However, unlike conventional models of ‘fortress conservation’, where ecosystems are isolated from human disturbances, the communities here were encouraged to coexist within the ecosystem. The local people were not forcibly relocated. Several opted for community-managed co-habitation, stressing the symbiotic and enduring relationship of humans with wildlife.

This type of conservation blended ecological restoration and socio-economic integration. The lions’ prey base — chital (spotted deer), nilgai (antelope), sambar (large deer), and feral cattle — was stabilised by improving grassland management and water conservation programmes. Studies show that the once degraded grassland ecosystems were revived with assistance from the Maldharis (local agropastoralists). Compensation schemes for livestock loss were strengthened, and grazing was regulated in buffer zones through participatory governance models. Gradually, communities realised and recognised the benefits derived from such developments.

The Maldharis and Siddis, whose cattle sometimes fell prey to lions, were compensated promptly, a factor that reduced animosity and increased acceptance of lions. They also benefited economically through eco-tourism, grazing rights, and improved access to water and fodder, making this a rare example of conservation where predator and pastoralist thrive together.

Lions Recolonise

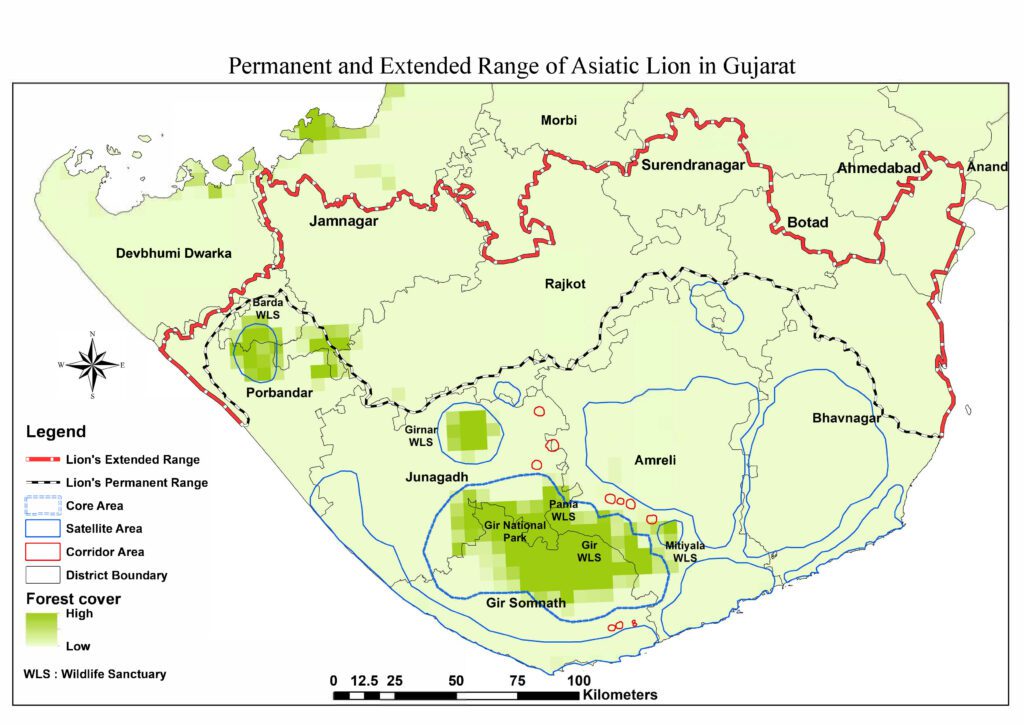

With improved habitat, something remarkable was noticed around Gir. Lions began dispersing out of Gir, colonising grasslands, agricultural fields, and coastal scrublands in Amreli, Bhavnagar, Junagadh, and Porbandar. They returned, after 30 years to their old home, the Girnar landscape, a patch of 179 km2 area with degraded forests located 50 km away from Gir National Park and Sanctuary.

This was due to the protection and eco-restoration work undertaken in Girnar forest. Today, there are 54 lions in Girnar, now a wildlife sanctuary. The current Asiatic lion distribution spans over 35,000 km², far beyond Gir forest. This natural expansion occurred without translocation, suggesting that lion populations were ecologically saturated in Gir and had begun reclaiming their former range with the eco-restoration and habitat improvement work taken up in the region. The systematic lion estimations efforts every five years enabled a strong scientific foundation for tracking trends.

Community involvement was deepened through awareness initiatives and investment in infrastructure like secured wells and machchans (platforms on trees to observer wildlife), and schemes like Vanya Prani Mitra (friends of the forest). Institutions such as the Gujarat State Lion Conservation Society (GSLCS) and specialised units like the Task Force Division and Wildlife Crime Cell ensured effective coordination, enforcement, and reinvestment into conservation priorities.

The forest and wildlife teams were motivated to take pride in this restoration work. The May 2025 survey highlighted the impact of such efforts. Not only has the lion count risen, the recorded presence of huge lion prides indicates presence of healthy prey base and limited human wildlife conflict.

Lessons for Global Community

The success of Asiatic lion conservation in Gujarat offers vital lessons:

- Conservation without human displacement is possible.

- Apex predators can thrive in multi-use landscapes.

- Community participation isn’t just a token gesture but a cornerstone for ecological resilience.

- Long-term systematic lion estimations and prey-base monitoring ensure adaptive management.

This conservation model can be an example for the world showcasing how a predator species at the brink of extinction not only survived but reclaimed its range autonomously, through habitat restoration. The recovery was not via regulation but with active participation of the local community. This programme did not require captive breeding support.

The Asiatic lions in Gujarat reclaimed lost habitat without fences or large displacement of people — an unprecedented feat in drought-prone, semi-arid and densely populated landscapes.

Author

-

Mr Bharat Lal is the Secretary General of the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), India. He is the Founder Mission Director of the National Jal Jeevan Mission, a programme to ensure clean tap water to every rural household in the country. He has been involved at the highest-level of policymaking and is well-known for his innovative thinking and problem-solving approach. His long association with forests and wildlife has given him deep insights into India’s conservation issues. He has co-authored two books, Tigers and Tribes: A Silent Conversation and Hidden Treasures: India’s Heritage in Tiger Reserves that exhibit the conservation ethos of tribal communities and their contribution towards sustaining the rich biodiversity of India.

View all posts