Preserving Nature Makes Smart Economics

Many of us admire big cats and other wild species for

their extraordinary beauty and the richness they add

to the world. They are fierce, endangered, and vital

to the ecosystems they help balance. But preserving

nature is also a livelihood for a growing number of people around

the world — especially in places where other opportunities are

scarce.

Preserving nature underpins hundreds of millions of jobs

globally. Forestry supports 50 million workers. Small-scale fisheries

sustain up to 500 million. Nature-based tourism, one of the fastest growing sectors in global travel, employs millions more — often in

regions where few other sources of income exist.

In these areas, nature is not just beautiful. It’s bankable. It

provides the first step on the ladder to the middle class — a step

that communities can build without destroying the ecosystems they

depend on.

Big cats offer a powerful lens to understand this dynamic.

Today, big cats roam in 95 countries across Asia, Africa, and

the Americas. Their story mirrors the challenges and choices

of development — a mix of progress, missed opportunities, and

cautionary tales. These apex predators often share their landscapes

with some of the world’s poorest communities. As climate shocks

intensify — floods, droughts, land degradation — natural resources

become scarcer. Conflict follows: big cats attack livestock, and

sometimes people. In turn, people retaliate, either to protect their

livelihoods or to profit from the illegal wildlife trade.

And the profits are high. The global illegal wildlife trade is

thriving, and big cat parts remain especially lucrative. That’s why

we work with law enforcement partners through the International

Consortium to Combat Wildlife Crime. Together, we help countries

dismantle the high-reward, low-risk dynamics that fuel wildlife

crime — from crime scenes to courtroom steps. Strengthening

governance in this way is not just good conservation; it’s smart

development policy.

But this is not a story of decline. It’s a story of potential — and

of progress.

In Nepal, the tiger population has tripled over the past two

decades, while forest cover has doubled. Crucially, that conservation

success is creating livelihoods. Our research shows that 45% of

international visitors come to Nepal to experience its natural beauty.

Around Chitwan National Park — home to 128 of the country’s 355

tigers — tourism-related jobs now employ 3% of the working-age

population. That’s not just spending — it’s economic lift. Each

dollar from a tourist grows by nearly 80% as it moves through local

jobs, services, and supply chains.

In Bangladesh, a mix of anti-poaching patrols, fencing, and

community engagement has helped boost tiger populations

without a rise in human-wildlife conflict. In Uganda, former poachers are now trained wildlife rangers, tracking lions in national

parks and turning conservation into steady work. In Mexico, jaguar

cubs are being rehabilitated and released into the wild, backed by

foundations that support both nature and local communities.

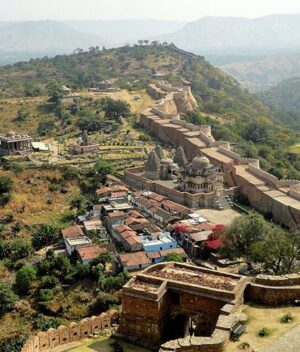

India — home to five species of big cats: leopard, lion, snow

leopard, tiger, and cheetah — has gone even further. It has built a

model of nature-positive development that lifts both biodiversity

and GDP. India hosts the world’s largest tiger population and has

revived the Asiatic lion through Project Lion. These achievements

now fuel a booming tourism sector, with marquee tiger parks

like Ranthambore emerging as engines of economic growth.

Ranthambore alone attracted over 650,000 visitors in 2023–24 —

a number growing by up to 15% year-on-year — creating jobs and

nurturing local talent among forest-dependent communities.

The ripple effects are real. Nature-based tourism brings income,

sparks entrepreneurship, and creates jobs — especially in rural

areas. Global research we’ve conducted shows that every dollar

invested in national parks delivers an economic return of at least six

times the original investment.

This success wasn’t accidental. It came from deliberate strategies

to integrate conservation into development — across three pillars: managing nature, building businesses around it, and sharing the

benefits. The World Bank Group helped champion this model

through the Global Tiger Initiative, launched in 2008, which united

13 tiger-range countries to craft national action plans — a milestone

that culminated in the 2010 St Petersburg Tiger Summit. India’s

recent launch of the International Big Cat Alliance (IBCA) builds

on that legacy — enabling countries especially across the Global

South to share knowledge and scale solutions. Its collaboration with

the Sankala Foundation to publish BigCats magazine is one more

example of homegrown leadership and innovation.

Preserving nature is smart economics. It creates jobs where few

others exist. It opens doors to inclusive growth. And it strengthens

the foundations for a better, more sustainable future.

No species tells that story more powerfully than the big cats.

This article was originally published in the Big Cats Magazine May-June 2025. Subscribe to receive your own copy Here.

Authors

-

Mr Ajay Banga is the President of the World Bank Group. He is the first person of South Asian ancestry to hold the position. At the World Bank, he has led the adoption of a new vision and mission for the organisation to create a world free of poverty, on a liveable planet. Under his leadership, the Bankhas undertaken a broad set of reforms to boost lending capacity, simplify operations, and deliver development solutions that are practical, scalable, and impactful.

View all posts -

Mr Robert bruce served as the 11th president of the World Bank (2007-2012). He has also held positions as the Managing Director of Goldman Sachs, the United States Deputy Secretary of State, and the US Trade Representative. Since ending his term with the World Bank, Mr Robert has been a senior fellow at Harvard’s Belfer Centre for Science and International Affairs.

View all posts